Back

by Peter de La Fuente

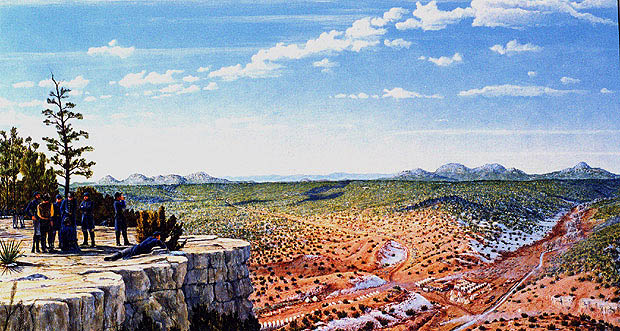

This painting illustrates a moment in the Civil War that is relatively obscure, although it is considered by many to have had a significant impact on the final outcome of the war. The sight is Johnson's Ranch in Apache Canyon, New Mexico, at about 2:00 PM on March 28, 1862.

The scene depicts Major John Chivington of the 1st Colorado Volunteers and his men on the edge of Glorieta Mesa overlooking Johnson's Ranch, planning the attack and total destruction of the lightly guarded camp and wagon train of the Confederates. These Rebels were the 4th, 5th, and 6th Texas Mounted Volunteers under the command of General Henry H. Sibley, (inventor of the widely used Sibley tent and stove). General Sibley intended to push north past Santa Fe to take Fort Union in northeastern New Mexico, replenish his supplies, and then continue into Colorado to take the rich gold fields for the Confederacy. From there, Sibley's plan was to head west, to California, where badly needed shipping ports could be established. Gold, and an overland route for raw materials back to the South were an exciting prospect. However, the surprise attack on the wagon train depicted here effectively stopped the Confederate campaign in the southwest.

The conquest of the New Mexico Territory by Confederate Texans began in the summer of 1861, when the 2nd Regiment, Texas Mounted Rifles, under Lt. Col. John Baylor came up the Rio Grande valley to Mesilla, New Mexico, claiming the bottom third of the New Mexico Territory-which included present day Arizona-for the Confederacy. In early 1862, Sibley's Mounted Volunteers joined with Baylor's forces, and numbering about 3200 men, began their march up the Rio Grande toward the Union outpost of Fort Craig.

The Union forces in New Mexico were commanded by Col. Edward R.S. Canby, who awaited the advancing Texans from the well fortified Fort Craig, south of San Antonio, NM along with about 3800 men. General Sibley quickly realized he could not take the fort. His attempts to engage the enemy outside the fort failed. The Confederates crossed the Rio Grande and made a dry camp on a plateau across the river from Fort Craig. The next morning the Confederates continued north to a crossing at Val Verde, a wide grassy area dotted with cottonwoods in the Rio Grande flood plain. It was here on February 21, 1862, that the first engagement occurred. Union troops met the advancing Confederates, and a vicious battle ensued. This was the only time that mounted lancers were actually deployed during the Civil War. The Texans finally drove the Federals from the field after a group of New Mexico Volunteers panicked and ran, leaving an artillery battery behind. For the Texans, the victory was hollow, as supplies were low, and their wagon train had suffered damage at the hands of Union troops. Sibley decided to bypass Fort Craig, and continue north to Albuquerque.

On March 2, 1862 a virtually unopposed Confederate

Army occupied Albuquerque, though still critically low on supplies, as

most stores and supplies in the town had previously been removed or

destroyed by the Federals. Basic provisions were finally

scrounged, and the army continued north to Santa Fe. The

capital city was taken without incident, as the Federal forces had

withdrawn to Fort Union. Again supplies had been removed by

the Federals.

Fort Union, on the Santa Fe Trail to Colorado had been well

supplied by Col. Canby. General Sibley knew this, and he knew

that he had to take the fort and replenish his supplies if he was to

continue. The Texans made their way along the Santa Fe Trail in the

cold March wind and snow, making camp at Johnson's Ranch in Apache

Canyon, some fifteen miles from Santa Fe.

Col. Canby had requested additional troops from Colorado. William Gilpin, first Governor of the Territory of Colorado, responded quickly, dispatching a group of 1st Colorado Volunteers to Fort Union. Word of the "Pikes Peakers" from Denver City marching from Fort Union soon reached the Rebels, who remained confident that both the fort and its ample supplies would soon be theirs. The Colorado Volunteers under Col. John Slough, as well as several companies of regulars from Fort Union and some New Mexico Volunteers, totaling about 1500 men left Fort Union to engage the enemy on the trail from Santa Fe. An advance party of about 400 men under Major John Chivington arrived at Koslowski's Ranch, near the Pecos Pueblo ruins on the evening of March 25. News of the Confederate camp ahead at Johnson's Ranch was awaiting them. Early the next morning, Chivington and his men marched along the Santa Fe Trail past the village of Glorieta, and down Apache Canyon toward the Confederate camp. A comparably sized Rebel party under Major Charles Pyron was scouting Apache Canyon, and was surprised by the Union forces. Chivington ordered an immediate attack, and after a heated battle, the stunned Texans were driven back to their camp at Johnson's Ranch. Fearing the presence of a stronger Confederate force, Major Chivington and his men along with some seventy Confederate prisoners marched back to Kozlowski's Ranch.

March 27, 1862 passed with the Confederates waiting at Johnson's Ranch, the narrow pass defended by sharpshooters on each side, cannon on a central knoll, and a hurriedly constructed earthen breastworks. All day the Rebels waited, and the enemy never came. At Koslowski's Ranch, Col. Slough and the rest of the forces from Ft. Union joined Major Chivington and his men.

Early in the morning of March 28, the entire Texan

army of some 1300 men set out eastward along the Santa Fe Trail toward

Glorieta. At about the same time that morning, the Union army

left camp and began marching west. After a few miles, one

third of the troops, under Major Chivington, split from the column and

followed a trail up the side of Glorieta Mesa, with the intention of

outflanking the Texans after the main column under Col. Slough had

engaged them. The main column continued on to Pigeon's Ranch,

a stage stop and brothel run by Alexander Pigeon, who had a reputation

for his great enthusiasm and hospitality. Here, Col. Slough

halted his troops and let them rest, sending a scouting party

ahead. The scouting party had not traveled a half mile before

they encountered the advance Confederate troops with the main force on

their heels, marching down the Santa Fe Trail. Word was sent

back to Slough, and the men were hurried forward. The

fighting was furious. The Union disadvantage in manpower was

made up for in spirit, and the constant expectation that Chivington and

his men would be attacking the enemy from behind at any time.

Casualties were heavy on both sides as the outnumbered Federals were

gradually pushed back to Pigeon's Ranch.

Meanwhile, Major Chivington and his men, guided by Lt. Col. Manuel Antonio Chavez, of the 2nd New Mexico Volunteers had reached the top of Glorieta mesa, where they soon left the main trail and followed faint tracks through dense pinon and juniper forest. Finally, they emerged on a rock ledge overlooking Johnson's Ranch, and saw the entire Confederate wagon train some four hundred feet below. Lt. Col. Chavez said to Major Chivington at this point, "You are right on top them." They had totally missed the flank of the enemy, but found themselves looking down on some eighty wagons, with horses, teamsters, a hospital...a lone six-pounder canon on a knoll was aimed eastward through the narrow pass toward Glorieta. There was a strange emptiness and calm to the camp. The teamsters rested near their wagons. The fewer than fifty soldiers left to protect the wagon train were relaxed, holding foot races, totally oblivious to any threat from the top of the precipitous mountainside that formed what had seemed to be a natural fortress to the east. Major Chivington and his men spent at least an hour on top of the mesa. The Major was concerned about a hidden force waiting in ambush, but finally decided that the destruction of the wagon train alone was worth the risk. The soldiers were ordered down the steep side of the mesa. The shale and lose earth proved difficult, and rock slides alerted the confederates below. By then, Colorado Captain Edward Wynkoop's men were on a shelf directly above the knoll with the canon. "Who are you below there?" asked one of Wynkoop's men across the narrow arroyo. "Texans, god damn you!" answered one of the Confederate artillery men. "We want you!" came the response, as the bullets flew. The cannon fired two rounds into the hillside before it was abandoned. The teamsters jumped on any available mount, and scurried up the trail to Santa Fe. Many of the Texan soldiers did the same. After reaching the bottom of the canyon, the Union troops marched forward in anticipation of a greater force. When none presented itself, the destruction began. The cannon was spiked, and tumbled down the knoll. Every wagon was ransacked, then set ablaze. The entire train of 80 wagons was utterly destroyed. An ammunition wagon blew up with such intensity that it caused the only Union casualty of the raid. The men then climbed back up the steep cliff, fearing the return of the enemy, and began the long march back to Pigeon's Ranch in diminishing daylight and increasing cold.

As they reached the main road that they had followed up the side of the mesa that morning, Chivington and his men were met by a messenger from Col. Slough, directing them to proceed to Koslowski's rather than Pigeon's Ranch. Apparently heavy casualties at Pigeon's Ranch had forced Slough to retreat. The Confederates had taken the battlefield. Col. Chavez, who knew the mesa well and had guided the troops to Johnson's Ranch that morning, refused to take responsibility for leading the troops back to Kozlowski's by a route that avoided the road near Pigeon's Ranch, where the Confederates now camped. The company Chaplain came forward. He was a large figure on a white horse, known as Padre Polaco, a Priest of Polish decent, who had served at the tiny church in the village of Ojo de la Vaca, just to the south of them on the mesa. He knew the mesa well, and offered to lead the troops back to Koslowski's Ranch, keeping them out of sight of the camping Confederate army. The snow began to fall as they marched in darkness. At times the enemy campfires were visible below. The column arrived at back at Kozlowski's at 10.00 PM.

The Texan's apparent success on the battlefield again was hollow. Their wagon train had been so thoroughly destroyed by the Union soldiers that they had no food, ammunition, or shelter. They borrowed shovels from the Federals to bury their dead. With no supplies or equipment, the Texans straggled back to Santa Fe, where some sick or wounded soldiers were taken in and nursed by Louisa Hawkins Canby, the wife of the Union commander. General Sibley and his remaining forces began their retreat down the Rio Grande to El Paso. Cannons and equipment were buried or discarded along the way. The long retreat on foot was full of hardship for the Texans. Col. Canby's Federal troops followed, keeping them moving south to El Paso. By May, 1862, General Sibley had left New Mexico. This marked the end of the southwestern campaign, the westernmost of the Civil War, and ended New Mexico's role in the Civil War.

ABOUT THE PAINTING:

The Johnson Ranch illustration was painted from the actual

spot where these soldiers stood. The construction of the

railroad and Interstate 25 has considerably widened and changed the

pass, and none of the original ranch buildings are standing.

Some of the landscape and the Johnson ranch house were recreated based

on early photographs and a drawing of the pass, made in a journal by

one of the Confederate soldiers who was at Johnson's Ranch.

The medium used in the original painting is egg tempera. This ancient technique of egg yolk and pure pigment on a panel coated with a sanded animal skin glue gesso, was widely used by early Italian painters in the 1400's. It has a remarkable luminosity, unlike any other medium, and it has proven to last for centuries. The artist's grandfather, Peter Hurd pioneered the use of the medium in this country in the 1920's, and taught it to other members of the Wyeth clan. Andrew Wyeth used it. John McCoy used it, and later on, even N.C. Wyeth used the medium.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Peter de La Fuente is a fourth generation artist from the well known Wyeth Hurd family of artists. His grandfather was artist Peter Hurd, and his grandmother was artist Henriette Wyeth, (eldest daughter of artist-illustrator N.C. Wyeth). Peter grew up on his family's ranch in southern New Mexico, and now lives in Santa Fe.

"This has been a fascinating project! I credit my son, Peter Convers, for getting me excited about the Civil War in New Mexico in the first place. Also many thanks to Dr. Don E. Alberts, whose personal insight and help was extremely valuable to me on this project. I highly recommend Dr. Alberts' latest book: The Battle of Glorieta-Union Victory in the West, Texas A&M University Press, 1998; as well as his previous book on the subject, Rebels on the Rio Grande-The Civil War Journals of A.B. Peticolas, Merit Press, 1993."

This certifies that "The Civil War in New Mexico" is

a signed, limited edition four color

reproduction. The edition has been limited to a

total of 725 impressions. 700 of these are signed and

numbered, and 25 are artist's proofs. The plates have since

been destroyed by the printer. No future editions will be

published. All copyrights are reserved by the artist.

Wyeth Hurd Gallery

P.O. Box 4154, Santa Fe, NM 87502

(505) 989-8380